Baseball was played in Washington, D.C., at the intersection of Georgia and Florida Avenues for 70 years, beginning in 1891, up through the end of the 1961 season. The original ballpark, called Boundary Field because it was located on Boundary Road (now Florida Avenue) at the District of Columbia’s former city limits, was home in 1891 to the Washington Senators of the American Association, and from 1892 to 1899 to the National League Washington Senators.

With the beginning of the American League in 1901, the American League Washington Senators began play at American League Park (I) which was located in Northeast Washington at the intersection of Florida Avenue, H Street, and Bladensburg Road in what is now the Trinidad Neighborhood (thanks to alert reader Geoffrey Hatchard).

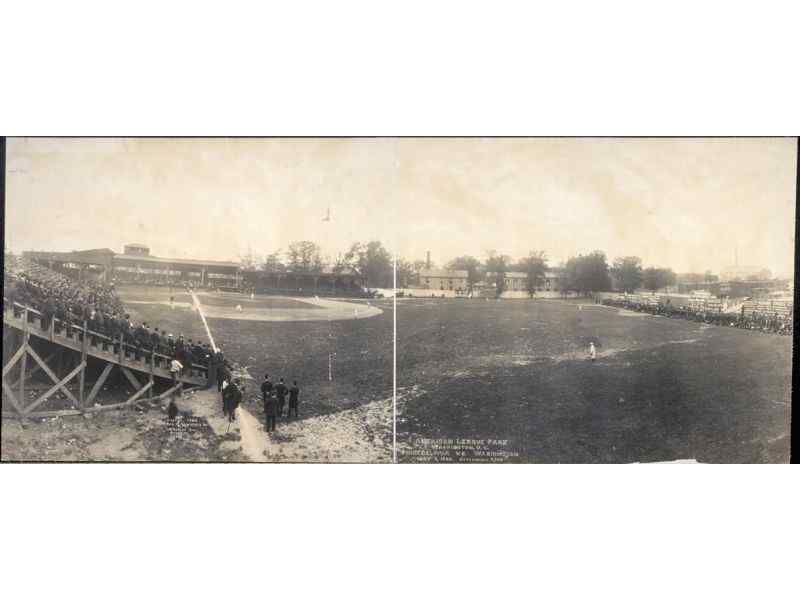

In 1904, the American League Washington Senators moved to the Boundary Field location, making it their new home ballpark. Known also as Nationals Park, the park was constructed almost entirely of wood.

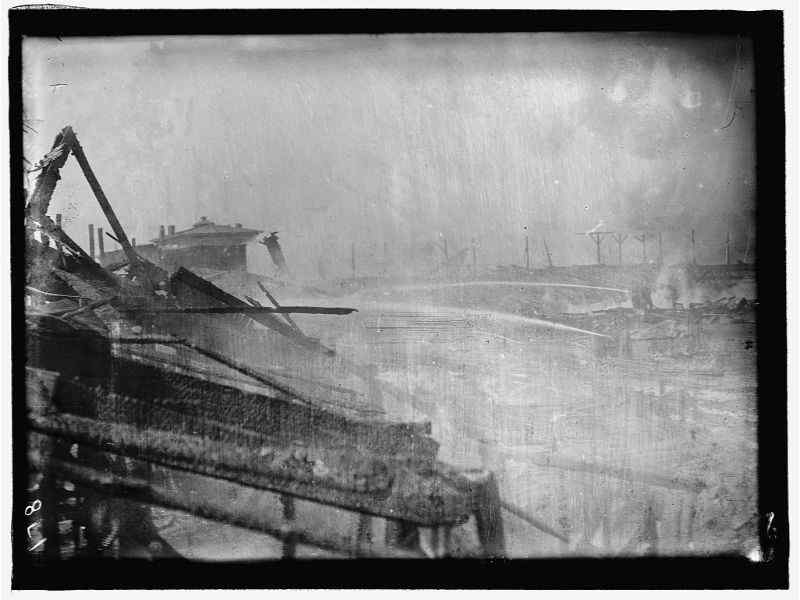

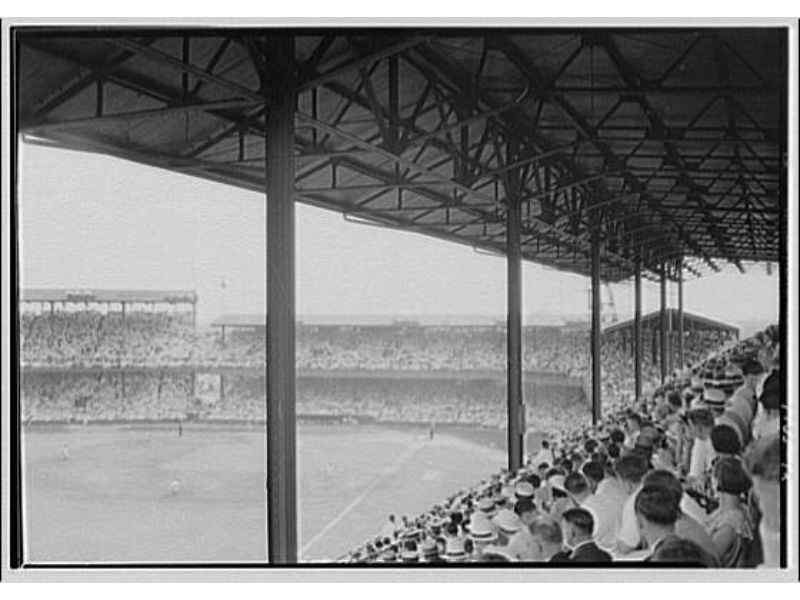

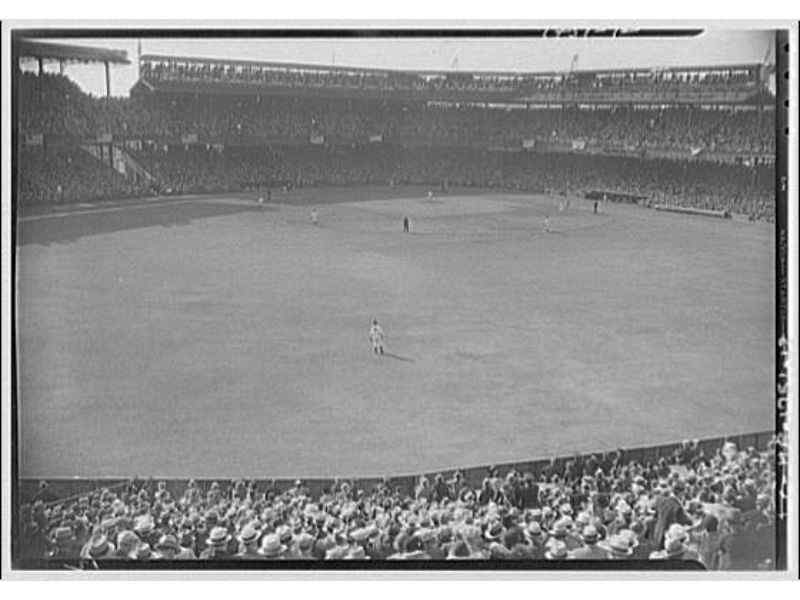

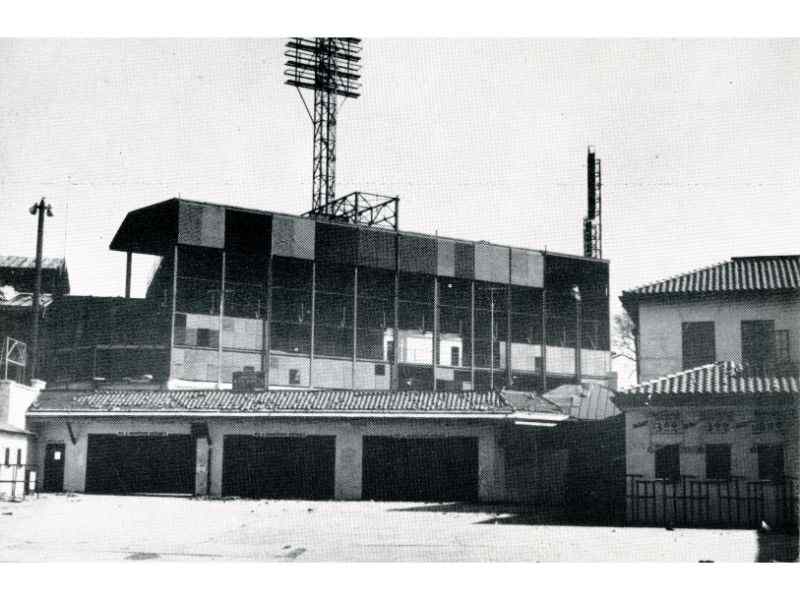

A fire on March 17, 1911 (caused by a plumbers lamp), destroyed the grandstand and a new concrete and steel stadium was built in its place.

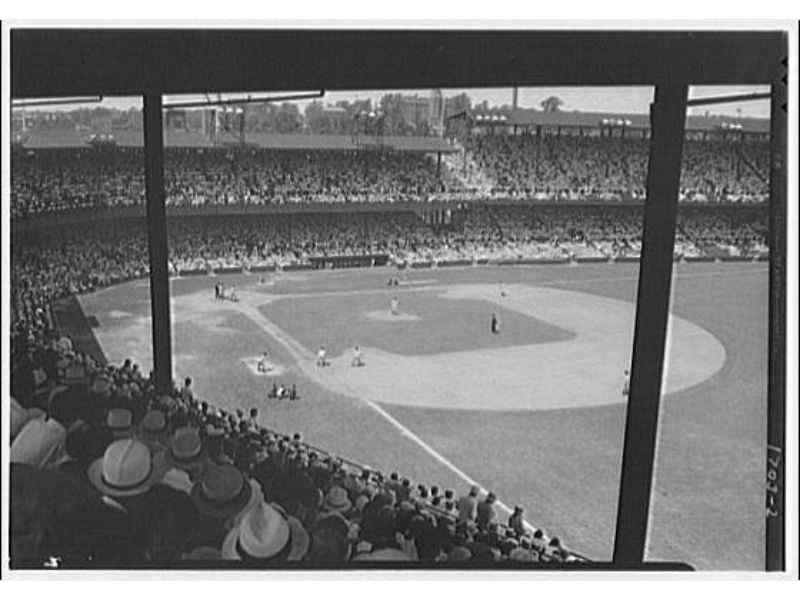

The new ballpark was also known as Nationals Park, up until 1920 when the venue was renamed Griffith Stadium in honor of Clark Griffith , the Washington Senator’s manager turned owner.

The Senators played at Griffith Stadium up through 1960, when, after the season ended, the team relocated to Minnesota. The 1961 expansion Washington Senators played at Griffith Stadium in 1961, moving to D.C. Stadium (later renamed Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium) in 1962.

Griffith Stadium also served as home field for the Negro National League Homestead Grays from 1940 until 1948, that team splitting their home games between Washington and Pittsburgh. The National Football League Washington Redskins likewise played at Griffith Stadium from 1937 until 1960.

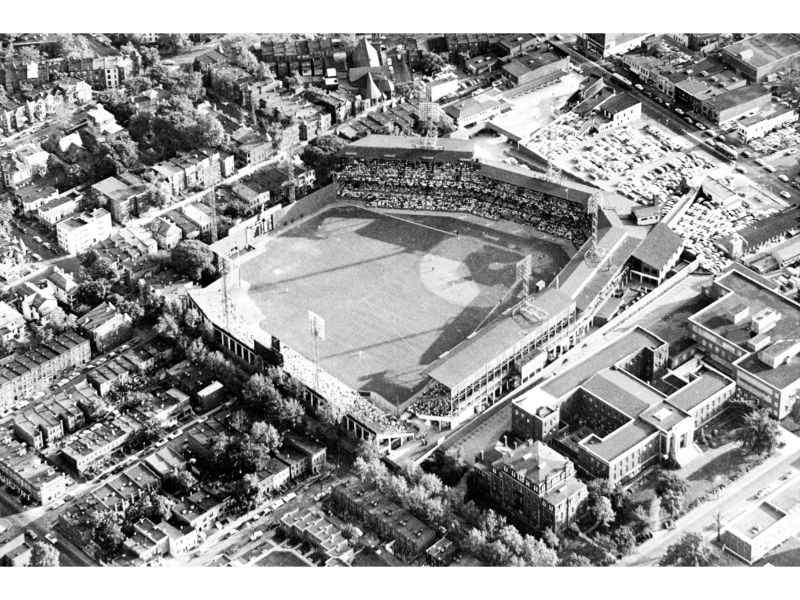

Home plate at Griffith Stadium was located near the intersection of Georgia Avenue and V Street, N.W.

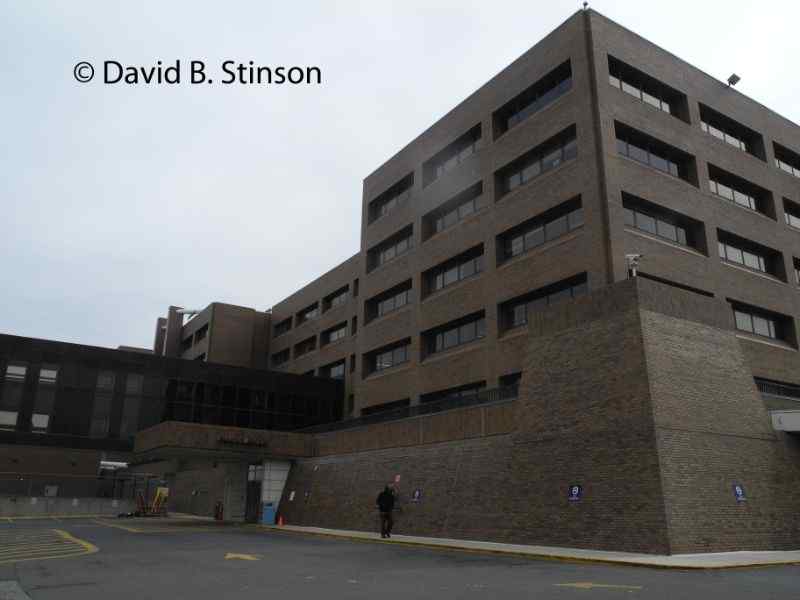

Howard University Hospital now occupies the site, the main hospital building sitting in the approximate footprint of Griffith Stadium.

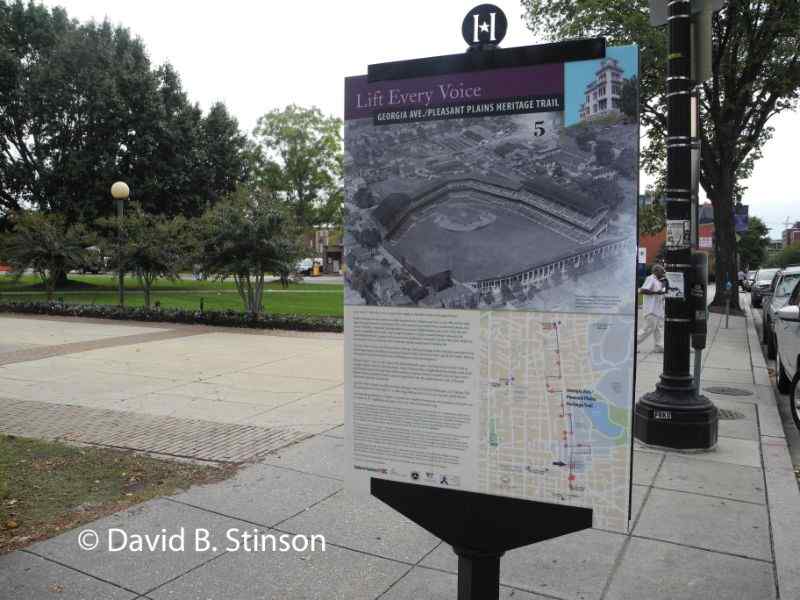

Signs posted in front of Howard University Hospital along Georgia Avenue honor the memory of Griffith Stadium.

The reverse side of the above sign recognizes significant moments in the ballpark’s history.

First base paralleled Georgia Avenue, angling away from Georgia Avenue toward U Street.

A ticket booth as well as the grandstand entrance once sat at the site.

Several row houses that sat in the shadow of the right field grandstand remain at the site along U Street.

Right field to the center field corner paralleled U Street.

Buildings that once sat in the shadow of the right field fence still remain at the site as well along U Street.

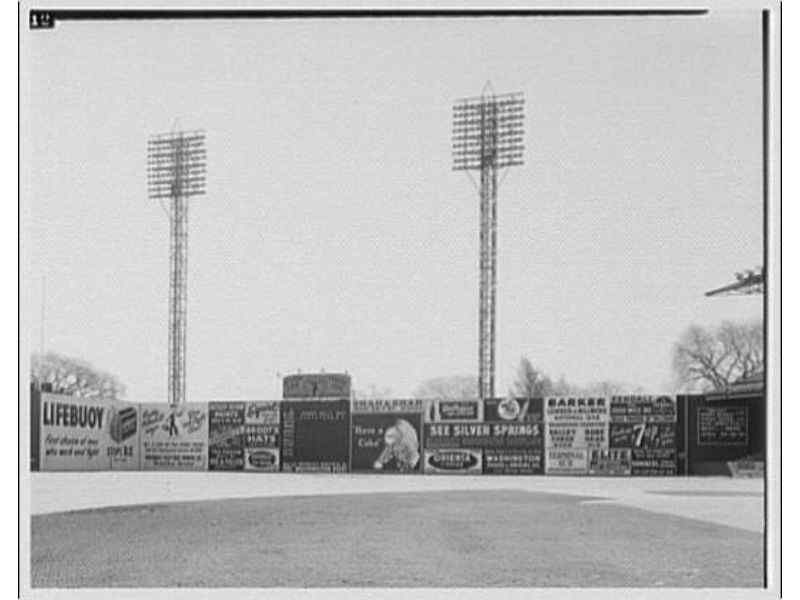

Griffith Stadium’s center field fence was infamous for its quirky indentation at the center field corner. Behind that fence sat several row houses, which the ball club unsuccessfully had attempted to purchase from their owners. Two of those row houses remain at the site.

In addition to those row houses was a large oak tree that actually spread across the top of the center field fence. Although that tree is now gone, there is a smaller tree at the site today, planted in approximately the same spot.

Griffith Stadium’s left field fence and bleachers paralleled 5th Street. That area is now a parking lot that runs along the back side of Howard University Hospital.

Third base ran parallel to what is now an alley between the hospital and buildings that front W Street.

Across the alley paralleling third base are several hospital buildings that date from the time of Griffith Stadium, including the College of Medicine.

Several other buildings that sit near the former site have a connection with the ballpark as well. The row house at 434 Oakdale Place is the spot where Mickey Mantle’s famous 565 foot home run off Senator’s pitcher Chuck Stobbs on April 17, 1953, landed. Ten year old Donald Dunaway, who was attending the game and watched the ball sail over his head, found the ball in the backyard of the row house.

Another building of note is the Wonder Bread Factory that was located at 641 S Street, N.W., just two blocks south of Griffith Stadium. The smell of bread baking at the factory often filled the air during games. The building today retains its original facade and serves the local art community by providing exhibition space.

Given the ballpark’s location in the Nation’s Capitol, Griffith Stadium played host to many of the nation’s famous Americans. Presidents from William Howard Taft to Richard Nixon (then Vice President) threw out ceremonial first pitches to start the baseball season.

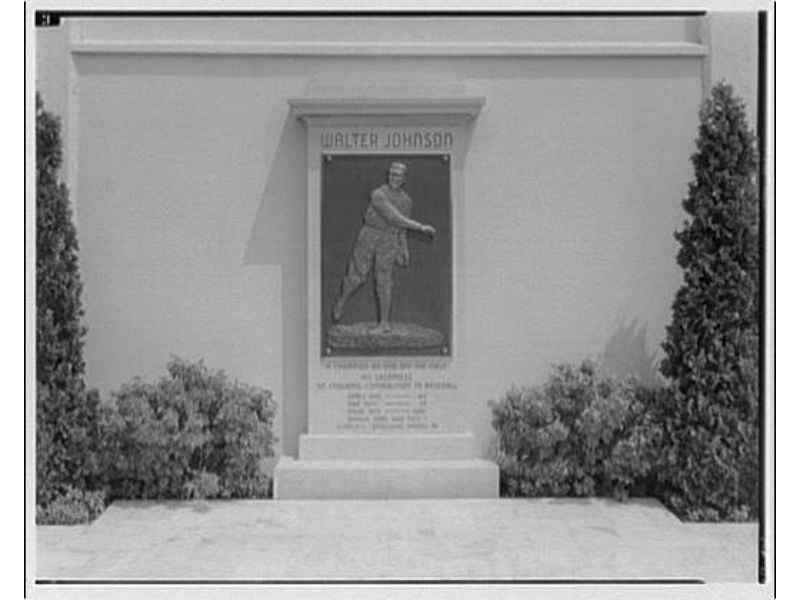

No baseball player best epitomized the Senators of the Griffith Stadium era than Hall of Famer Walter Johnson, who not only pitched for the team for over 20 years, but also was a radio announcer for the Senators after he retired from baseball. Upon his death in 1946, the team placed a memorial to Johnson at Griffith Stadium.

That memorial, a small piece of Griffith Stadium, resides today near the athletic fields at Walter Johnson High School in Bethesda, Maryland.

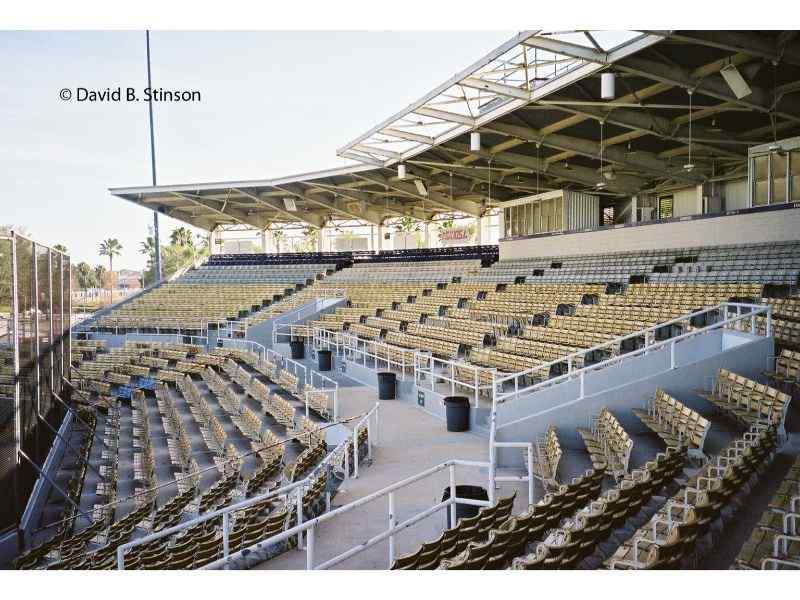

When Griffith Stadium was demolished in 1965, stadium seats were shipped to Orlando, Florida, and installed in Tinker Field, which at the time was the Spring Training home of Calvin Griffith’s Minnesota Twins. Those relics of Washington, D.C., baseball, remained at Tinker Field until the stadium was demolished and some of those seats were sold to collectors by the City of Orlando.

Although Griffith Stadium has been a lost ballpark since its demolition in 1965, there still is much to see at the site today. Inside the hospital’s main entrance on Georgia Avenue is a small museum in one of the conference rooms that honors Griffith Stadium and significant events from its history. In a corridor just beyond the conference room is the actual location of home plate, which is marked on the hallway floor along with the outline of the batters box.

The former site of Griffith Stadium is located only three and a half miles north of the Washington Nationals current ballpark – the new Nationals Park, and is well worth a visit for any of the team’s current fans who are interested in experiencing a little of D.C.’s baseball past.